Last night on my flight home to Berlin from Copenhagen I started reading “Principles” by Ray Dalio. Holy shit, it’s incredible. Dalio’s thinking is original, incisive and relentless. I don’t want to get too breathless but for a certain type of person at a certain moment this book is like a bomb going off in your head. Some context: over the past year I have been trying to learn about finance and investing. Money is obviously a topic that’s important to many of us but growing up in a liberal, bourgeois and waspy intellectual family it was a topic that was actively not discussed. Whatever the social mores that encourages people to not think about discuss or take seriously the topic of money and finance, I see it as a serious disadvantage. I try to be very transparent with my kids about money and discuss it in clear terms with them so they see at as a tool and means to an end, rather than as something tied up in all these ideas of class, propriety, self-worth and whatever complex emotions and social customs lead people to not want to talk about it. Honestly even writing about the topic here I feel a bit uncomfortable, a strange, and probably un-useful dynamic. I read Tony Robbin’s “Money: Master The Game” and from there moved on to reading Warren Buffet’s “The Essays of Warren Buffet”. Robbin’s made reference to Dalio who came across as interesting and so I bought “Principles” as well, but sat on it and didn’t read it. After reading the Buffet book I was ready for a break from reading about financial instruments, which while I’m interested to understand, I find dry.

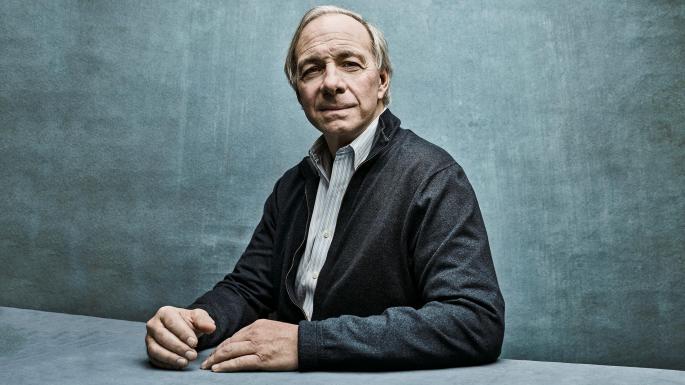

I expected Dalio’s book to continue in the same vein and so put off reading it for a while. Last night I needed something for my flight and it was the book I had unread on my Kindle app on my phone, so I gave it a try. I really wish I had started earlier. Firstly, although Dalio is clearly a brilliant financier, this is really not a finance book. For those unfamiliar with Dalio, he grew up in Long Island, NY. His father was a jazz musician and mother a home-maker. He became interested in the markets at a young age, went to Harvard Business School and then after working various Wall Street jobs started Bridgewater associates as a research firm in a two bedroom apartment, before growing it into one of the world’s largest and most successful hedge funds with tens of billions under management. He has actively not sought the spotlight which may be why many, including myself haven’t heard of him, but after tremendous success in what he describes as the ‘third stage’ of his life he has shifted his focus to giving back. He’s signed the giving pledge along with Gates and Buffett and will gives a significant percentage of his wealth to charity, and has undertaken to distill and codify his learning in the process. This is where we arrive at “Principles”.

Dalio is a systems thinker par excellence. His primary mode of operation is to gather and record data, process it with algorithms (systems or formulas) and then reflect on what that processed output reveals in order to make informed decisions. Very early on he realized that he could analyze all of the inputs to a system, distill them into a set of rules and then model that system with various inputs. He initially did this with commodities markets, learning how the production of meat was informed by grain prices, how fast the various meat animals put on weight and how the various prices and inputs interacted with one another. He built this into a model using early personal computers and was able to make informed decisions about the prices of corn, meat and soy in the commodities markets to great success. He embraced digital technology and modeling early and has kept pace and extended his use as computing power increased exponentially. This is where this concept of cyborg decision making arises. Dalio guides the investment process at Bridgewater using a massive array of digital models of millions of data points, processed using artificial intelligence techniques which he then compares to the decision making arrived at by the human agents of the firm, including himself. The result is a kind of mental scaffolding in which the humans compare their intuitive and analytical understandings and beliefs about how markets will behave against the more objective and emotionless logic of the machine agents. This cyborg process of decision making allows for both agents in the process to play from their strengths. Humans have powerful intuition and ability to see gestalts, but can be blinded by bias or emotion, whereas machines have the incredible ability to compute and objectively score data. The results in terms of the financial performance of Bridgewater have been astounding.

Dalio advocates in his book for us all to encode and externalize our decision making in a set of principles which we write down and evaluate our intuition against. He obviously also is a great believer in data, and using data to inform decision making. Dalio is in my opinion a genius of process and systems. His powerful insight is that he on his own is incapable of making the most optimal decisions. He has therefore sought to support his decision making process with a powerful scaffolding of machine intelligence and also collaborative human intelligence in the form of his team. Dalio’s focus on radical open mindedness and radical transparency as it’s practiced in the company culture of Bridgewater is a whole additional topic worth discussion on it’s own, and you’ll probably be hearing more about it in these pages as the shockwaves of this book ripple through my brain. To get an idea for how radical his approach to managing people is he has been described in the press as a ‘hedge fund cult leader’. For me, the story and thinking of Dalio feels like a direct challenge that needs to be responded to. How do I incorporate this into what I do? In a sense I feel envious because the playing field he chose on which to deploy his brilliance, the financial markets, is one with such a clear scoring mechanism. Every idea you try has a clear goal, to earn financial profits and to protect against losses. So he has a wonderfully direct way to evaluate the validity of his ideas.

For those of us who choose other areas in which to play, like the arts, how can we incorporate this kind of thinking? I think this kind of cyborg relationship to technology is already upon us in many areas of our lives, with so much of what we do mediated by software. For Dalio he has used it to incredible effect. What is the equivalent of this for artists? Steve Jobs famously called the computer a bicycle for the mind. Incidentally Dalio was a great fan of Jobs and spent significant time trying to understand and model his thinking after his death, seeing parallels between their worldviews. I think the full Jobs quote is a good way to end this piece.

“I think one of the things that really separates us from the high primates is that we’re tool builders. I read a study that measured the efficiency of locomotion for various species on the planet. The condor used the least energy to move a kilometer. And, humans came in with a rather unimpressive showing, about a third of the way down the list. It was not too proud a showing for the crown of creation. So, that didn’t look so good. But, then somebody at Scientific American had the insight to test the efficiency of locomotion for a man on a bicycle. And, a man on a bicycle, a human on a bicycle, blew the condor away, completely off the top of the charts.

And that’s what a computer is to me. What a computer is to me is it’s the most remarkable tool that we’ve ever come up with, and it’s the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.” ~ Steve Jobs (via brainpickings)