Lately I’ve been playing Michael Brough’s game Cinco Paus. Like all of his work, it’s singular, deeply considered and rewards thoughtful exploration. I’ve played many of his games but probably have spent the most time with 868-Hack and Imbroglio. I’m not very good at any of Brough’s games but enjoy them a great deal. Brough’s games share many tropes with the Roguelike genre but sidestep some of it’s sprawling maximalist complexity by transporting the genre to mobile platforms. Roguelikes, for those unfamiliar, are characterized by turn based gameplay, simple (often text based) graphics, randomly generated levels and a focus on emergent, combinatorial complexity, among other things. Being a community of pedantic nerds there is in fact an official agreed upon convention for ‘true’ genre membership which is called the Berlin Interpretation, created at the Internation Roguelike Development Conference of 2008. The creation of this type of ‘official’ genre definition is fairly unique among stylistic communities which usually police genre membership in a more informal and haphazard way, so in that regard is sociologically interesting. In another regard genre policing is deeply boring and horrible but I digress.

In many ways Brough’s games actually do satisfy the strictures of the Berlin Interpretation but discussing that for more than a sentence would make this piece terribly boring. Instead I’d like to think through how the imposition of limits, the shrinking of an idea to a tiny phone screen allows thought to crystallize in beautiful ways, looking specifically at Cinco Paus. For people who enjoy thinking about games as systems of rules, roguelikes and their adjacent offshoots represent a kind of pure expression of this. Because the game is randomized every time, it’s impossible to memorize sequences of moves or ‘brute force’ ways to overcome challenges like looking up answers on the internet. Instead we have to try to understand the underlying system which gives rise to the unique experience of each playthrough and thereby increase our skill and progress deeper into the game.

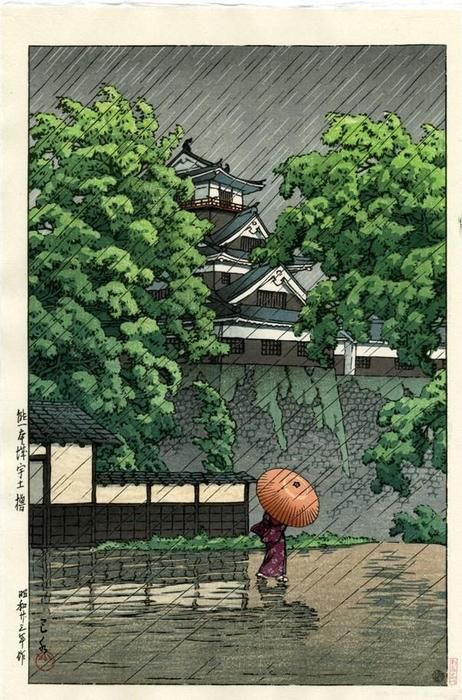

In Cinco Paus, Brough deploys the familiar roguelike trope of randomized the levels or (highly abstracted) dungeons that the player must explore but in a restrained, minimalist form. The game is made of five rooms which are composed of a grid of five by five squares. The levels are formed by placing walls randomly on the resulting grid, along with enemies (frogs, shrimp, chickens and ghosts) and items to collect. Many roguelike games spend a great deal of energy complicating these environments and treat exploring these generated dungeons as one of the main areas of interest. I myself have spent a great deal of time thinking about this in the creation of my tool called Strata, which aims to help game developers using Unity make roguelike games. Instead of focusing on exploring a physical space Brough instead chooses in Cinco Paus to explore the combinatorial space of rules, embodied in the games weapons: five magic wands.

You start the game with five wands arrayed across the top of the screen, each imbued with magical powers. Importantly, you do not know what those powers are, and they change every game. The wand always shoots a ray in a straight line across the board, but what that ray will do is unknown. For example sometimes it might pass through walls, kill frogs but not shrimp and teleport things it hits. Each of these wand powers is represented by a tiny drawing which appears next to it as it’s powers are activated. Whether the wand is shot up, down, left or right also impacts how the powers are activated and revealed. As we begin the game we need to first try to use all our wands in various situations to understand what they do. As it becomes more clear we can try to deploy them in skillful ways to navigate the dungeon, collect points and survive.

The idea of discovering the hidden properties of a magical item is a theme from Roguelike history, dating back to the game which spawned the genre, Rogue. In Rogue you could find potions as you explored the dungeon. They would have a color, but that color would not indicate the effect initially. Instead you either had to use it to find out what it did or use a magic scroll to identify it. Some potions had helpful effects, like healing, and others had unhelpful effects, like blindness or confusion. Roguelikes being the tricky complicated mazes that they are, of course these potions were not universally helpful or unhelpful, for example in some cases you could escape being killed by a medusa by being blind. In Cinco Paus Brough takes this concept of identifying unknown items and essentially makes a whole game out of it. By taking one concept from this larger, more maximally complex genre and stripping away or minimizing almost everything else he allows us to focus deeply on a single idea. The result is wonderful and rewards time invested with moments of surprise and delight. The more you understand all it’s moving parts, the more you can combine and experiment with them in a way that feels both extremely playful and rewarding. The fact that this type of rich strategic play is available on a mobile phone screen with a simple swipe and drag input system is illuminating.

Brough’s games are all a kind of masterclass in restrained, yet rich game design but it’s worth discussing the aesthetic packaging as well. Brough does all his own visual art and sound and the result is idiosyncratic and not in the style of ‘traditional polished game art’. For me this personal, auteurist approach makes the games feel all the more like a singular work of art, but some have criticized the approach, finding it amateurish. In Cinco Paus, in my opinion, Brough reaches a new plateau with both the art and sound that hopefully will quiet some of his detractors. For the art he continues in the drawing style of Imbroglio but with a more refined and beautiful use of color and line. The music and sound which function together as a single collage are perhaps one of my most favorite aspects of the game. Using processed guitar and burbling synthesizer gloop, heavy in spacious echo and reverb, the result is unselfconsciously beautiful and surreal at the same time. In Imbroglio there’s a wonderful mechanic in which each space moved by the player triggers a single guitar note or sample, creating a very satisfying, participatory procedural musical experience, but due to some of the melodic choices Brough makes he continuously undermines the harmonic structure with dissonant flourishes. This feels to me like a kind of self-consciousness, a desire to not make something too harmonically ‘simple’ or easily pleasant, but in Imbroglio it rang false to me. In Cinco Paus Brough has allowed the music to be beautiful and focuses the weirdness on spatialization and texture, which for me works wonderfully and is a choice I’m delighted in.

There isn’t a smooth way to introduce this fact, but in Cinco Paus, as the title may indicate all text in the game is inexplicably in Portugese. This choice, for those of us who don’t read the language, contributes further to the exotic, inscrutable and alien air of the game. I assume this adding of a layer of indistinction was the goal as we the (I assume) mostly English speaking players try to puzzle out the unfamiliar words. It’s a bizarre and interesting choice, which goes well with the game’s boldly ornamental and kitschy choice of typography. There may be some attempt to sabotage easy use of search-engines as well, since the items are not clearly named being identified only by visual icons.

If you’re interested to play Cinco Paus, as you can imagine I recommend you do, you can find links to it on Brough’s website. My Twitter friend Raigan Burns also kindly recommended to me some great resources on learning to play (or play better in my case) that will take you beyond the basics when you are ready. I also recommend this effusive article by NYU’s Frank Lantz, who is clearly also a fan.